After graduating from a Bachelor of Visual Communication, beading artist Camille Laddawan completed a Masters of Art Therapy, which sparked her interest in non-verbal styles of communication.

Throughout her twenties, Camille had set out following the deep artistic urges she’d experienced since childhood, slowly trying to find her medium. She experimented with photorealistic drawing, abstract oil painting and sculpture until she came to beading at the beginning of 2020.

Over the past 18 months, Camille has taught herself beading processes and techniques, slowly developing a Tone Code – her own symbology of colours and marks that each correspond to a letter of the English alphabet. Using this personal coda, she occasionally threads messages into her finished pieces. Other designs are simply dictated by pattern and palette.

Camille cites a varied selection of influences: mathematician Max Dehn who taught about the intersection of art, nature and maths; philosopher Susanne Langer for her unusual writings about symbolism and emotion; Paul Klee for his technical yet dreamlike painted poetry; polymath Joseph Albers for his work in colour and geometry; and linguist Roy Harris, whose research challenges the typical understanding of how communication, language and sign are formed.

In short, Camille’s art is deep and enveloping; both stirringly personal and yet expansive and engulfing. Her beaded creations act as a personal cipher to an increasingly abstract world.

Hello Camille! You live and breathe an artistic life. What first brought you to bead artistry?

When I was three years old at Montessori school, I lost a beaded coin purse. It was tiny, could fit inside my palm, and it was coloured yellow with pink and green flowers — perfect for putting seeds, a marble, or a spare lolly in. I loved it and its magical feel.

Other than that, my family and education have shaped my artistic background. My mother is a scientific and natural history artist, who taught painting and drawing at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne. Growing up, my sister was a talented violinist, and my grandmother was a photojournalist and an aid worker for children. The people surrounding my family were either in botany, science, art, drama or music.

Throughout high school I was extremely shy, so I engaged in a lot of sport and athletics, and hid away in the art room on the forgotten top floor (places that didn’t require me to talk). The school I went to offered life drawing and was rich in art supplies, so I made the most of the facilities and often stayed after school until 6pm, working around the cleaners, trying to master photorealism. Upon completing VCE I wanted to study a Bachelor of Fine Arts, but my family was concerned I wouldn’t earn a living, so I wasn’t allowed!

Your studio space is so calm and beautiful, can you tell me about it?

My studio is located at the front of my home in Collingwood, where I live with my partner, housemates, and Ru our dog. The property is an old shop and residence built in the 1900s, and renovated about 15 years ago by my uncle Kim, who is a prolific carpenter and furniture maker. The house is filled with his intricate woodwork. The building shoulders up to the Collingwood North post office and looks out at one of the oldest brothels in Victoria, an oil painter’s house, and another mysterious terrace (we don’t really know what goes on there).

My studio is a narrow, two-by-four meter wood-panelled room, which faces north. My desk is pushed up against the front window, which looks out onto Johnston Street; to people collecting their letters and parcels, people riding past on motorised scooters with their loud and tinny speakers, and the eclectic foot traffic of the ragged and faithful Collingwood.

What is the process of making one of your pieces?

I use high-quality glass seed beads, strong thread, extra fine beading needles, and a loom. Beading is a committed process that requires full attention, patience, and stamina. It’s hard to converse with people, as I’m consistently counting each bead and row, so I listen to Radio National or music while I work. This mathematical element sets a rhythm, and my hands are constantly attuning to the tension of the threads. Beading for me is simple and calming, with its various sequences of repetitions and patterns. I think this strange desire to devote so much time organising tens of thousands of minuscule beads and threads into rows gives balance to my mind, which tends to wander.

Once the beading is finished, I loosen the screws on the sides of the loom and the beading sinks off the loom. When holding them in your hands, they feel heavy and slinky. Then I name each work, slide them into a glassine envelope, stamp my Thai name on them and write out a certificate of authenticity. Overall, the beadings appear delicate, but they are very tough, somewhat like Hauberk chain mail.

Why are you drawn to beads?

Beads provide one of the earliest examples of symbolic thinking. Symbolic thought is the capacity to allow one thing to represent another. Beads have been used in many cultures throughout the world for tens of thousands of years as objects of trade and commerce, as well as for personal adornment. My interest in beads is because of this connection to symbolic thinking.

Can you explain the Tone Code you devised to inscribe messages into your pieces?

Tone Code is a visual alphabet I devised using combinations of light and dark tones to differentiate letters and punctuation. I wanted to find a way to connect with language and conceal messages in my work, so I began by researching non-verbal languages like Morse Code. Tone Code creates a dual purpose within my beadings, as viewers can understand and appreciate the way emotion and expression are conveyed aesthetically, as well as literally.

What does art-making mean to you, and what do you hope to communicate?

For me, art-making is a gentle and constant state of the search for or creation of meaning. The beauty in art is that it connects with more mysterious and complex ways of communicating. I am interested in how we can access language and communication from different perspectives using aesthetics.

The 26 letters of the English alphabet are oral symbols that are both powerfully functional and tailored to the colonial history that predominates Australia and globalised communication. The English language, with its left-to-right scanning from top to bottom and cohesive, linear nature is restrictive, imperialistic and it can skew and prioritise certain ways of understanding the world.

Many people believe that written/oral language is a prerequisite for understanding; if you do not have the words then you do not understand yourself, the other or the subject. My beadings hope to prompt viewers to think about other ways in which language, storytelling, documentation, and information can be communicated.

Camille takes commissions for new works and sells existing pieces via email here or Instagram DM here. Learn more about her practice here.

Camille Laddawan in her studio, located at the front of the old shop she lives in in Collingwood. Photo – Roslyn Orlando.

Camille’s bead artistry is designed with colour, pattern and even her own visual alphabet. Photo – Camille Laddawan.

References line the walls. Photo – Roslyn Orlando.

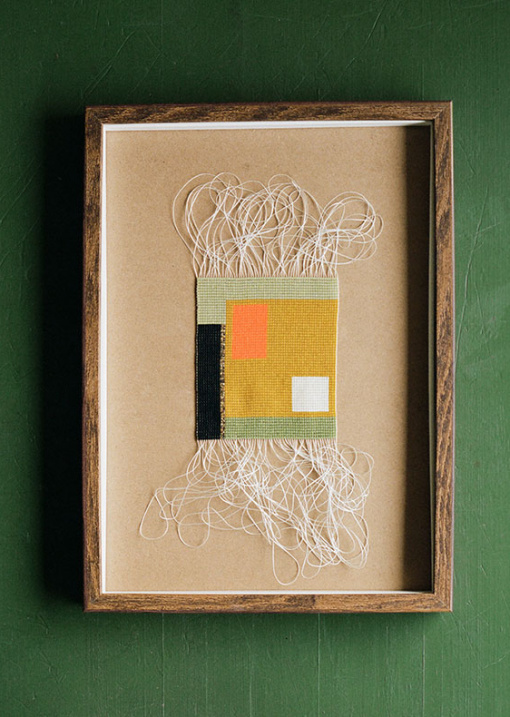

Finished pieces framed and hanging on the wall. Photo – Camille Laddawan.

Threading beads onto the loom. Photo – Roslyn Orlando.

Camille’s influences are mathematicians, linguistics, philosophers, artists and polymaths. The bead work is methodical and almost scientific. Photo – Camille Laddawan.

Her practice is slow, meditative and precise. Photo – Roslyn Orlando.

Camille devised her own visual alphabet called a Tone Code, so she could weave messages into her work. Photo – Roslyn Orlando.

For her first body of work, Camille collected letters and personal documents from three generations of her family, enshrining text fragments into her final beaded pieces. Photo – Camille Laddawan.

The documents she sourced were from all over the world: Perth, Thailand, Vietnam, Iran, Nepal, Greece, London and Melbourne. Photo – Camille Laddawan.

Each piece requires careful planning to match the final design. Photo – Roslyn Orlando.

Camille handthreads her designs with glass beads. Photo – Camille Laddawan.

Camille’s sunny studio at the front of the shopfront-turned-sharehouse she lives in. Photo – Camille Laddawan.

Objects and texts in the studio. Photo – Camille Laddawan.

A warped and shaggy finished piece. Photo – Camille Laddawan.

A piece containing text translated into Camille’s Tone Code sits framed next to other reference pieces in the studio. Photo – Camille Laddawan.

Photo – Camille Laddawan.

Serene Camille. Photo – Roslyn Orlando.